A Walk Through History

A Yale Scholar on the Streets of Mahanoy City

A Yale Scholar on the Streets of Mahanoy City

By Amber Lawrence

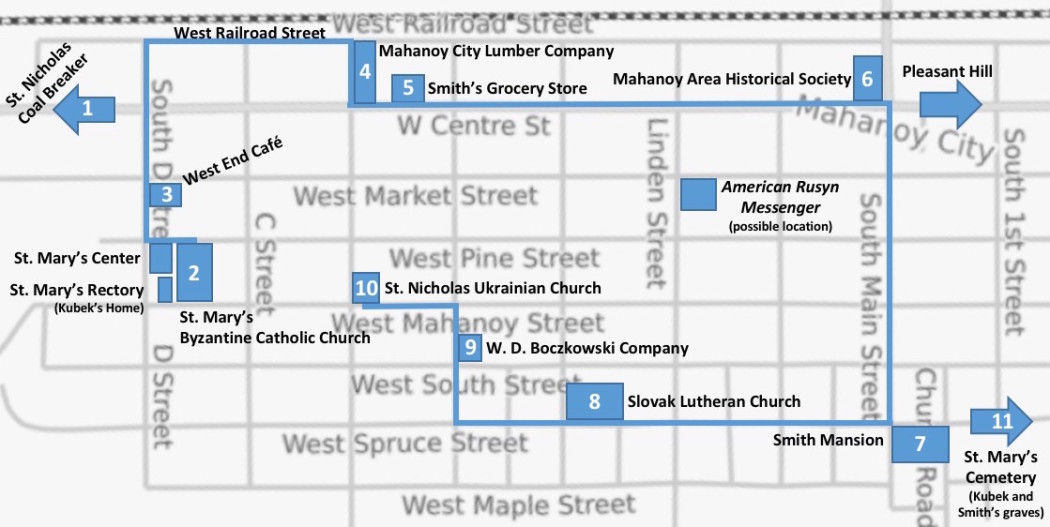

I was lucky enough to interview Yale scholar Nicholas Kupensky, a teacher and author who has studied Carpatho-Rusyn language and literature. I asked him a few questions about his life and career, and a walking tour he is working on based on the writings of Father Emil Kubek, who served as pastor of St. Mary’s Byzantine Catholic Church in Mahanoy City from 1904 to 1940.

Coal Cracker: What is your background?

Nicholas Kupensky: I was born in Youngstown, Ohio. My father’s family is of Polish ancestry. My mother’s side is Carpatho-Rusyn. I graduated from Bucknell University in 2007 with a triple major in Comparative Humanities, Russian, and English, and then started my Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University. I have been teaching at Bucknell since 2013 in Comparative Humanities and Russian Studies as a Visiting Assistant Professor. This academic year, I’ll be finishing my dissertation at Yale.

CC: I heard that you had written for a youth-led newspaper like Coal Cracker. Can you tell me about that experience and what got you into writing?

NK: This is a funny story. When I was in middle school, my parents had bought a new Gateway computer that came with some free publishing software, so I started to play around with it and realized that I could publish my own newspaper. I wrote all the stories, made all the graphics, did all of the design, etc. and then I started selling it at school for a quarter (or maybe it was a dollar). I ended up getting into a lot of trouble for this, but my middle school language arts teacher (Gina Tabacca) saw that the quality of the writing and design were pretty high (even if the things I was writing about were less than ideal). She arranged for me to meet with Guy Coviello, the editor of our local newspaper (the Warren Tribune Chronicle), which happened to have an award-winning teen section, called Page One.

I lived at Page One when I was in high school. I started out as a news reporter, then got really interested in graphic design and pagination, and then was one of the editors by the time I graduated. A lot of nights I would go to the Tribune even if I didn’t have anything specific to work on since I just liked being in the newsroom. One night, the main paper’s graphic designer called in sick (or maybe was on vacation?), so I pitched in and started working for the main paper as a freelancer as well. I think by the time I graduated from high school, I had published or designed well over 100 stories and pages.

CC: How did you become interested in your chosen field of Carpatho-Rusyn languages and literature?

NK: When I was growing up, my grandmother lived with us, and she was a very devout Orthodox Christian. She went to St. John’s Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Church in Sharon, PA a lot — it felt like every day — and a lot of the times she took me along with her. She also spoke Russian and Carpatho-Rusyn (although I didn’t know what a Carpatho-Rusyn was at the time). Because I didn’t really understand the complex differences between ethnic groups at the time. I assumed that our family was Russian since that was the only country I had ever heard about in school, and so I started to study Russian when I was a student at Bucknell.

I completely fell in love with Russian language and even more so Russian literature. I studied abroad in Moscow in the spring of 2006. I applied to go to graduate school in Russian literature and was accepted. I spent a year between undergrad and graduate school in Moscow again (2007-2008), and have had a number of very cool jobs there. I taught English to the Russian Olympic Team, taught a number of courses at the Russian State University for the Humanities, was the tutor of some high level businessmen and a current member of Putin’s cabinet. But the more I learned about Russian history, the more I realized something didn’t add up.

When my grandmother died in 2007, I found the villages where her parents lived, and they were both from what is now southern Poland. My grandfather’s family came from the village of Čirč in what is now eastern Slovakia and had been there for 300 years. These areas had never been part of Russia, but I couldn’t really figure out who they were.

I was at a Slavic conference in 2008 and just happened to be walking through the book dealer’s section, when I came upon a booth sponsored by the Carpatho-Rusyn Research Center (I happen to be the Vice President of the organization now). They had a large map that showed all of the villages where Carpatho-Rusyns have historically lived, and I found my grandparents villages on it. And then I realized I wasn’t Russian but Carpatho-Rusyn.

In 2011, I studied abroad in Prešov, Slovakia for three weeks at the Studium Carpato-Ruthenorum, which is the only program available where you can learn about Carpatho-Rusyn history and learn Carpatho-Rusyn language. And long story short, I got hooked.

Father Emil Kubek

CC: How did you become aware of Father Kubek’s work?

NK: In 2014, I was a summer scholar at Columbia University in the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute called “America’s East Central Europeans: Migration and Memory.” My research project was on the Carpatho-Rusyn literature published in American newspapers, and I came across a number of Emil Kubek’s poems in a Carpatho-Rusyn newspaper called Den’ (The Day). Of all the Carpatho-Rusyn American literature that I had read, I thought his work was by far the best and that he had a great sense of humor. After reading a bit more about him, I saw that he lived and worked in Mahanoy City, which is only about an hour from Bucknell.

In the spring of 2015, Bucknell’s Action Research program sent out a call for research projects about Pennsylvania’s Coal Region, and I jumped at the opportunity. Together with one of my students Erin Frey ’17, who is a triple major in Comparative Humanities, English and Economics, we applied for the grant and got it, and then I started reading everything by him that I could find.

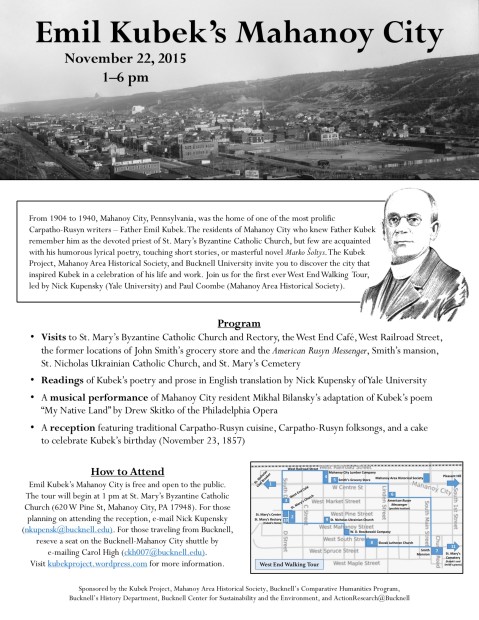

CC: Can you describe the walking tour project that you’re working on?

NK: Since its inception, the concept of our project has grown. We’ve launched a website called “The Emil Kubek Project,” which will house a number of related ongoing projects. The three that I’m working on now are:

2) Kubek Work

I’m trying to collect as much of Kubek’s writing as I can — both in English and in Carpatho-Rusyn. This includes his novel, short stories, poems, journalism, sermons, letters to the editor, his dictionary, etc. What isn’t available in English, I’m going to gradually start translating, and then annotate the texts to provide information that an average reader wouldn’t necessarily know.

3) Kubek Archive

Together with the Mahanoy Area Historical Society, we’re going to use the Kubek Project as a comprehensive bibliography of works about him as well. The Historical Society has a number of newspaper articles about him (and other Carpatho-Rusyns in Mahanoy City), and we’re trying to bring them all together, publish what we can digitally, and what we can’t publish online can be accessed in person at the Historical Society.

CC: A bit off topic, but this issue of Coal Cracker will be out during the Halloween season and the word Carpatho reminds us of the Carpathian Mountains and the legend of Dracula. How is this legend viewed from your perspective as a Carpatho-Rusyn scholar?

NK: Honestly, this is a pretty relevant question. When Slavs immigrated to the United States at the end of the 19th and early 20th century, they were often seen as less white than Anglo-Saxon Americans and often viewed as a threat to the American way of life, as if they were sucking the blood out of American communities. I suppose this metaphor works when you consider that Dracula (also published at the end of the 19th century) is this scary, threatening force that terrorizes the English-speaking world.

One of the projects Erin worked on was to do a discourse analysis of the Mt. Carmel newspapers and see how they wrote about the recent Slavic immigrants. She created a word cloud that shows the most frequently used words associated with the Slavs.

Here is a fragment from the walking tour explaining this:

This large diverse population of recent immigrants made Mahanoy City’s West End fertile ground for cultural misunderstandings and ethnic-inflected skirmishes, and local newspapers covered conflicts between Slavs and their neighbors with the sensationalist fervor of yellow journalism. The Mt. Carmel Daily News eagerly chronicled even the smallest of confrontations with dramatic copy fit for the tabloids. “Two men may die and one is badly hurt as a result of assaults by drunken Huns and Slavs in Wilkes-Barre,” reads an 1894 news brief. In 1896, Shamokin witnessed the “usual assault and battery tale of woe” when “a fracas between a party of Russian Poles and Slavs” resulted in three men being arrested. In a story from Whiting, Indiana, three men turned up dead when a “race war” erupted between a Slavic saloon keeper and his Hungarian and Italian customers. Another article tells the story of a “terrific race riot between Slavs and Polish miners and coke workers” that involved thirty men and women who ended up “covered with blood after the fracas” in Connellsville.

Local papers covered cultural misunderstandings even when they didn’t burst into violence. An article entitled “Case like Tower of Babel” describes a situation in which the newly-appointed rector of Shamokin’s Lithuanian and “Slavonian” churches was “perfectly willing to hear his people’s confessions,” but “it is impossible to make him understand” because he didn’t speak the same language as his parishioners.

While many of these stories likely have some degree of truth, the frequency with which they appeared suggests that many of them are overblown to play on the American public’s fear of these new immigrants, which, of course, would sell more papers. Indeed, the words most frequently used to describe “Slavs” in one local newspaper were “strike,” “shot,” “killed,” “murder,” and, above all, “foreign.”